Exploring Mandalay on a trishaw — Myanmar

Cars and motorcycles honk and speed past me, inches away from my body, leaving behind a trail of dust. At the front, Challu, unfazed by incoming traffic, disregard for road rules and the cacophony of engines, keeps pedalling. Driving a trishaw, after all, has been his breadwinner for more than 20 years.

Indigenous to Mandalay, trishaws are a dying mode of transportation, and Challu reckons that only 2000 are in use today. He's adamant about upgrading to a taxi, like his brother. His battered three-seat bicycle is a memento to a different era and a triumph of Myanmar entrepreneurship against the British.

According to Dr Tin Muang Kyi, a studious of Myanmar history, the trishaw came around during a period of political upheaval against the British colonisers. At a time when public transportation was scarce, a boycott of British products saw colonialist tram cars without passengers. Introduced by entrepreneurial locals, the trishaw became the preferred means of transportation.

Sitting for lunch, at a local joint, with a traditional Shan feast between us, we talked about ourselves and Myanmar. His story doesn't different from many other kids; receiving his education at a monastery, studying The Dhamma and learning English, choosing to leave after completing High school to work the family trade. As the conversation progressed, and we got to know each other better, it was clear the Challu wanted to say more about Myanmar than the common, textbook facts. His speech became bolder, with biting remarks about the way things are, and trying his best to explain the complex ethnic issues that have created instability and headaches to the newly elected democratic government.

"Do you want to give money to the people or the government?" The answer would determine which temples he would take us — and possibly his opinion of us. But it wasn't a hard choice, we were happy to promote local economy.

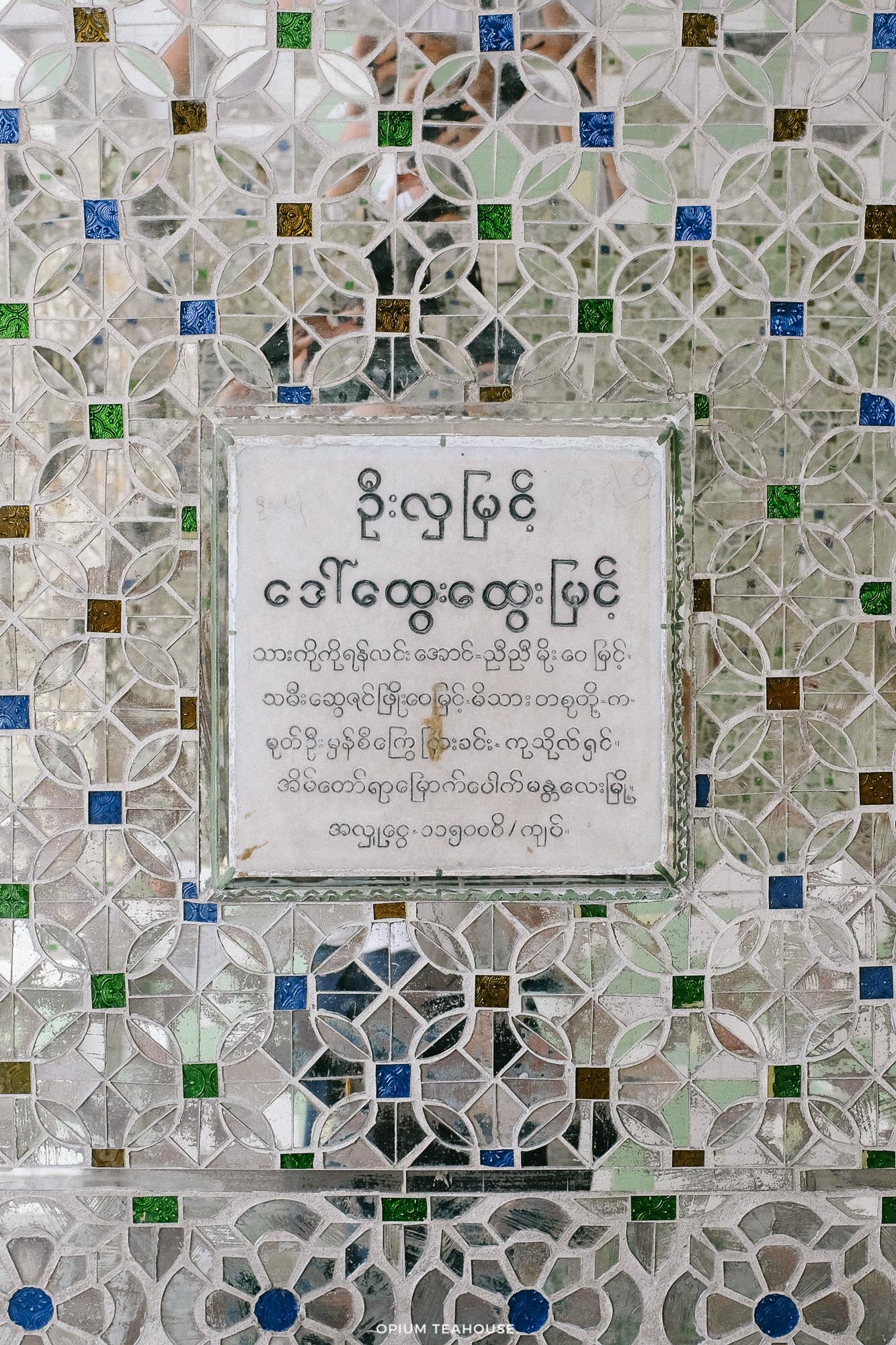

Dodging the 10.000K Mandalay temple pass, that has most tourists strategising their days to take maximum profit of, also appealed. Kuthodaw Paya — displaying the largest stone book in the world — Sandamuni Paya, Bo Bo Gyi Nat Shrine and Kyauk Taw Gyi Phayar, all in close proximity, were an appetiser for the sunset at the shimmering Sutaungpyae Paya, on top of Mandalay Hill.

Riding in the back seat of a trishaw can be discombobulating to western sensibilities, yet, it provides invaluable insights into the city's costumes: honking, on one hand, is not only to warn other drivers but to say hello and goodbye. It should be used liberally, at any time of the day and night. Foreigners, on the other, are still a rarity. And walking down the street or riding anything else besides an air conditioned, smoked window car, is carte blanche for locals to stare, wave and giggle at.

As I'm driven down the bumpy roads, for the last time, I can't help to smile continuously to the locals that drive by. The raw energy that Mandalay exudes might be off-putting to most visitors, but see past the noisy facade and you will find some of kindest, most curious people ever encountered.